This was a laborious and lengthy project, to which the great Mexican architect dedicated the utmost care with deeply religious devotion.

He even donated his professional services and partly financed the construction of this convent for a group of nuns who live lives of seclusion in devotion to St. Francis. Barragán admired the cult of St. Francis for simplicity and his appreciation of the beauty of nature.

The project involved restoration of the old convent and construction of a chapel.

The architect designed a new entrance from the street and set up the convent spaces around a long, narrow central cloister, which provides access to the sacristy, transept and chapel through side corridors.

This was a laborious and lengthy project, to which the great Mexican architect dedicated the utmost care with deeply religious devotion.

He even donated his professional services and partly financed the construction of this convent for a group of nuns who live lives of seclusion in devotion to St. Francis. Barragán admired the cult of St. Francis for simplicity and his appreciation of the beauty of nature.

The project involved restoration of the old convent and construction of a chapel.

The architect designed a new entrance from the street and set up the convent spaces around a long, narrow central cloister, which provides access to the sacristy, transept and chapel through side corridors.

The building does not stand out from the others around it on the outside, but inside one is continuously astounded by a series of expedients used in Barragán’s architectural method.

As in the great medieval monasteries, the architect rejects symmetry in search of emotional spaces marked and amplified by the light of the sun.

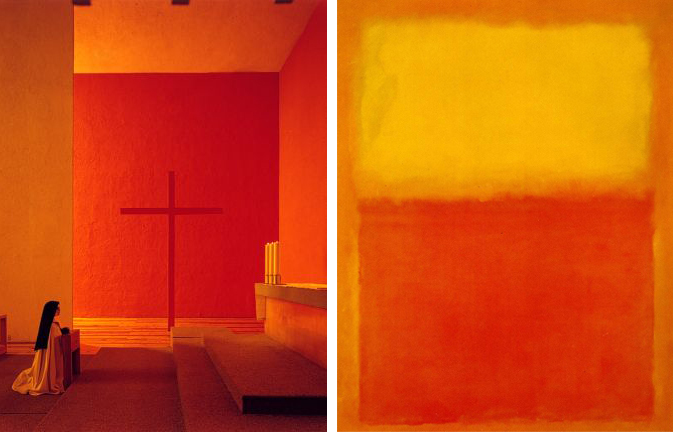

He uses textures and light to lend his constructions an amazing mysticism: the chapel walls have a rough, harsh texture and are painted bright lemon yellow.

The floor is covered with planks of wood, which help dematerialise the chapel by reflecting a honey-coloured light.

Two windows allow natural light to filter through, modifying it, so that it forms the space differently at different times of day: a square yellow cement grid at the back of the chapel and a slit running the full height of the chapel with golden panes of glass helps soften the daylight that floods the chapel.

A second light source, hidden from view, illuminates the large, slender orange-painted crucifix from the side, so that its shadow falls on the altar. The place of prayer for the secluded nuns is separated from the main chapel by a painted wooden grid, and has a lower ceiling which does not reach the rough chapel walls, letting golden sunlight flow in from above.

This is a mystical, transcendental space full of that “true Mexican spirit” that Barragán aimed for in the material nature of his works and in his use of colour.

He was fully aware of the importance of the mural painting tradition and the way walls are treated in Mexican art, and after his initial experimentation with Mediterranean style, the architect concentrated his attentions on treatment of the basic surfaces and planes in his constructions.

The vast surfaces of the coloured walls characterising Tlalpan Chapel are actually luminous screens that play with the physical substance of matter, calling up deep-seated, mysterious, enchanting sensations that go beyond concrete appearances.

Barragán designed every detail of the chapel, down to the vestments for the officiating priest, in an attempt to give form, light and colour to the abstract concepts of faith and the origin of human destiny.

The result is a space that continually refers back to an inner dimension where light, the origin of all things, reveals the magic of beauty.

Location: Tlalpan, Mexico City (1954–60)